Miss Silver Comes To Stay, by Patricia Wentworth (1949)

What’s this book about? Miss Maud Silver, retired governess and eagle-eyed private investigator — yes, really — goes to visit her old friend Cecilia Voycey in the country. A few days after she arrives in the village, however, James Lessiter, the unpleasant heir returning to come into the estate of the late Mrs. Lessiter quarrels with everyone in his vicinity and threatens them with various unpleasant consequences. As will be no surprise to connoisseurs of such behaviour, he is promptly murdered.

What’s this book about? Miss Maud Silver, retired governess and eagle-eyed private investigator — yes, really — goes to visit her old friend Cecilia Voycey in the country. A few days after she arrives in the village, however, James Lessiter, the unpleasant heir returning to come into the estate of the late Mrs. Lessiter quarrels with everyone in his vicinity and threatens them with various unpleasant consequences. As will be no surprise to connoisseurs of such behaviour, he is promptly murdered.

It seems as though everyone in the village has had an encounter with him in the hours before his death; as Lessiter’s heir, beautiful young Rietta Cray is suspected. There’s a beautiful middle-aged lady who has either been given or stolen some valuable furniture and knick-knacks from the late Mrs. Lessiter’s estate; Carr Robertson and his beautiful but empty-headed girlfriend Fancy Bell; and a host of minor characters from acidulous solicitors to talkative daily help, in sub-plots that range from blackmail to the whereabouts of a set of solid gold statuettes depicting the Seasons. Miss Silver must probe into both the social and economic relationships among all the players before bringing home the murder to a character whom the reader will probably not have suspected.

Why is this worth reading?

Why is this worth reading?

In order to answer that question for this specific book, I need to talk about all the Miss Silver novels. You’ll understand as we proceed. I have a very large library of paperbacks that’s mostly stacked up in boxes in a spare room; occasionally I open a box at random and see what I find. The latest such box contained a heap of some 19 volumes of Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver novels, and I had an experience that was rather like a Netflix binge. I’d read all the volumes before, of course, but I arranged them in date order and waded in, stopping to acquire the ones I couldn’t find in E-versions, and read Miss Silver from start to finish. It’s been a very interesting experience; I had the opportunity to make some large-scale observations about how Wentworth’s writing works, and what exactly she was trying to do with the Miss Silver brand.

In the past I have written briefly about my admiration for Wentworth’s command of a very specific type of writing. In every book in the series of 32 volumes published between 1928 and 1961, the same tiny elements are always present, again and again. We have a tour of Miss Silver’s sitting room, with specific references to things like Victorian reproductions and the rich peacock blues of her curtains, and dozens of silver-framed photographs of children (of clients whom she’d saved from the gallows). We get a description of Miss Silver’s clothing in tiny detail, complete to the exact colour of the bog-oak brooch and her Alexandra fringe under her hairnet, the velvet coatee that she wears in draughty country homes at dinner. Miss Silver has what’s called a hortatory cough — she coughs to reprove people for impropriety at least once in every book. She quotes the poetry of Tennyson, and pretty much always the same quotes (“The lust for gain/in the spirit of Cain,” for instance). We know the name of her long-time servant, her relationship with her former pupil and now young Scotland yard detective, demi-aristo Randal March, and the names of Randal’s supervisor’s daughters, the three Lamb girls. We see Miss Silver knit in the Continental style, with the needles held low in her lap. We see Miss Silver gently steering the lives of her two nieces, one “good” and one a flibbertigibbet who is a sore trial to her staid solicitor husband. And this mass of tiny detail is repeated and accreted in every single volume, over and over and over again, sometimes with tiny changes as time moves forward. If you like this sort of thing, well, this is the perfect series. If you find it evidence of a lack of creativity, that’s your privilege (I’d beg to differ, but I understand what prompts the opinion).

Miss Silver generally has the same effects upon murder plots and characters, over and over. She pretty much always straightens things out so that a beautiful young woman (frequently with long caramel-coloured eyelashes and “good eyes”) can marry the man whom she has misunderstood, or about whom she’s heard lies, or who repents of having left her years ago, without the threat of one or both of them being arrested for the murder. Frequently she meets people of different social classes; every book has upper-class suspects and lower-class witnesses, pretty much, although there are frequent instances of lower-class villains. In every encounter, she uses her mastery of a specific social interaction — the manners which an elderly Englishwoman of middle- and upper-class expects of people with whom she converses — and exploits good manners to investigate crimes. If she encounters rudeness, or an unwillingness to cooperate, she either coughs or in extreme cases dismisses a certain kind of loose-moraled young woman from her presence. She wheedles information out of tongue-tied housemaids that is unavailable to the police; she manipulates the village network of gossip and clacking tea-time tongues to get a wealth of detail about who said what when and to whom, and what they were wearing at the time. Since she has the respect and admiration of higher-ups, lower-level officers have to obey her, not that they aren’t leaping to do so anyway since she solves more murders among the upper classes than the average Metropolitan squad in a year.

Miss Silver generally has the same effects upon murder plots and characters, over and over. She pretty much always straightens things out so that a beautiful young woman (frequently with long caramel-coloured eyelashes and “good eyes”) can marry the man whom she has misunderstood, or about whom she’s heard lies, or who repents of having left her years ago, without the threat of one or both of them being arrested for the murder. Frequently she meets people of different social classes; every book has upper-class suspects and lower-class witnesses, pretty much, although there are frequent instances of lower-class villains. In every encounter, she uses her mastery of a specific social interaction — the manners which an elderly Englishwoman of middle- and upper-class expects of people with whom she converses — and exploits good manners to investigate crimes. If she encounters rudeness, or an unwillingness to cooperate, she either coughs or in extreme cases dismisses a certain kind of loose-moraled young woman from her presence. She wheedles information out of tongue-tied housemaids that is unavailable to the police; she manipulates the village network of gossip and clacking tea-time tongues to get a wealth of detail about who said what when and to whom, and what they were wearing at the time. Since she has the respect and admiration of higher-ups, lower-level officers have to obey her, not that they aren’t leaping to do so anyway since she solves more murders among the upper classes than the average Metropolitan squad in a year.

To me, this is the kind of book that is meant for a person who is relieving an experience of extreme youth; the delight in hearing a familiar story told in the same way, word for word, again and again. We all know of a child who must have the same book as a bedtime story over and over, and woe betide the guest reader who skips a page or gets a word wrong. I can’t explain what’s happening here in psychological terms, but I know it’s common and not pathological. It’s a yearning for the familiar, perhaps — a reassurance that some events are dependable and that no matter what horrible things happen, Miss Silver can step in and save the day, mete out punishment to the guilty, arrange it so that good people live happily ever after, and then vanish from the village tea-tables so that gossip will not continue to spread. So those are the stylistic considerations that have impressed me over the years.

My recent Silver binge, however, gave me a few insights that are struggling towards completeness; bear with me, but I have delved deeper than I’ve heretofore gone, and wanted to share my preliminary thoughts.

Foremost of what I no ticed was that — well, first you’ll have to accept that, generally speaking, Miss Silver novels are written for women readers. I think this is defensible; my experience behind the counter of a mystery bookstore leads me to believe that 90% of Miss Silver aficionados are intelligent middle-aged women (they appreciate the fineness of the language and a certain elevated air of social intercourse that permeates the novels, rather like Jane Austen). That is important as a premise, because my observation was that many of the plots involve situations where a woman is in jeopardy or difficulty. Again, not uncommon. But what I came to realize was that Wentworth has a trick of creating situations that a woman especially would experience as jeopardy, and she tells the story in a way that strikes a not wholly unpleasant fear into the hearts of women. In brief, she knows what would scare a woman and she knows how to tell that part of the story in a way that does scare a woman.

ticed was that — well, first you’ll have to accept that, generally speaking, Miss Silver novels are written for women readers. I think this is defensible; my experience behind the counter of a mystery bookstore leads me to believe that 90% of Miss Silver aficionados are intelligent middle-aged women (they appreciate the fineness of the language and a certain elevated air of social intercourse that permeates the novels, rather like Jane Austen). That is important as a premise, because my observation was that many of the plots involve situations where a woman is in jeopardy or difficulty. Again, not uncommon. But what I came to realize was that Wentworth has a trick of creating situations that a woman especially would experience as jeopardy, and she tells the story in a way that strikes a not wholly unpleasant fear into the hearts of women. In brief, she knows what would scare a woman and she knows how to tell that part of the story in a way that does scare a woman.

I might not yet have been precisely clear on this, but let me give an example sub-plot from the present volume. An upper-class woman whose husband has died and left her in reduced circumstances has been allowed to live in the Dower House on the estate of, as the story begins, the recently-deceased Mrs. Lessiter, her long-time friend. This woman (Catherine Welby) has become financially dependent upon the largesse of Mrs. Lessiter; a situation has arisen where Catherine has been allowed to use valuable and beautiful antiques to furnish the Dower House from Mrs. Lessiter’s holdings, over the course of decades. Catherine will maintain that these items were given to her; Mrs. Lessiter isn’t around to say differently. Many years ago, Mrs. Lessiter’s heir James was an unsuccessful bidder for her hand in marriage. Now, as Mrs. Lessiter’s estate is being settled, James reveals that his belief is that Catherine has stolen these items and is about to discover that she’s sold some of them to pay for her taste in luxuries. And he also reveals that he has located a memorandum in his late aunt’s papers that states that she loaned the items to Catherine. It seems as though he intends to ruin her, both socially and personally, by having her prosecuted for theft. But is he actually putting pressure on her to submit to his amorous desires? Perhaps luckily, he is murdered before we find out.

Now, I suggest this is the kind of thing that a woman really understands. Catherine herself regards her actions as merely what she needs to do to survive. (In a delightful moment that is very revealing of character, when confessing what she regards as her peccadillos, she says, “Well, a woman must dress.”). But it’s not so much that she’ll be prosecuted for theft, it’s that she will be socially ruined and may even have to submit to James sexually (although to be fair this is not more than glancingly suggested; she might marry him to prevent scandal).

Other volumes have woman-centred subplots that are equally feminine and bitter. One that stuck with me for a long, long time was a gentlewoman of advanced years who was starving to death and selling her furniture, piece by piece, to stay alive — but cannot bring herself to mention it to anyone or get social assistance. Another features a young woman who is under the thumb of her domineering mother, who wants to spend all the family’s capital on high living and fakes a heart attack any time the daughter’s lover comes close to marrying her. This is not the brutality of a James Hadley Chase, but perhaps, to a certain kind of reader, the prospect of devoting one’s life to one’s domineering mother until one’s marriage chances are over is a horrible situation that has echoes in her own life. This is not about being pistol-whipped, but I think Patricia Wentworth definitely understands the death of a thousand little cuts.

And so my main in sight is the presence of this type of plotting, which I think Patricia Wentworth does very well indeed. There is a frequent theme of women being constrained by social situations, social pressures and the niceties of keeping a good face on things, that results in women’s lives being wasted and ruined. But there are other recurring themes and even plot structures. There are beautiful young female orphans; some needy, some spiteful and vicious and greedy. There is a recurring theme of two beautiful young women, one of whom is “county” and beautiful but not striking, and the other is glamorous like an exotic poisonous orchid. A woman’s romance with a handsome young man is frustrated, again and again, by an elderly female relative. Men must marry money to maintain their ancestral estates, regardless of whom they love. A domineering woman controls the family’s money and ruins everyone’s lives. A lower-class woman marries the wrong man and is brutalized into committing crimes, or enabling them. Collections of family jewelry are responsible for multiple murders; family heirlooms and even hidden treasure troves are concealed and there is a deadly race to possess them. (And Miss Silver usually mentions the lust for gain in the spirit of Cain.) A foolish middle-aged woman contracts a romantic attachment to the wrong man. And one unusual theme recurs at least twice as the central premise of a book; if Wentworth tells us about a distinctive and striking garment, like the eponymous Chinese Shawl or a coat with a pattern of huge checks, the next person to borrow that garment is found dead after having been mistaken for its owner.

sight is the presence of this type of plotting, which I think Patricia Wentworth does very well indeed. There is a frequent theme of women being constrained by social situations, social pressures and the niceties of keeping a good face on things, that results in women’s lives being wasted and ruined. But there are other recurring themes and even plot structures. There are beautiful young female orphans; some needy, some spiteful and vicious and greedy. There is a recurring theme of two beautiful young women, one of whom is “county” and beautiful but not striking, and the other is glamorous like an exotic poisonous orchid. A woman’s romance with a handsome young man is frustrated, again and again, by an elderly female relative. Men must marry money to maintain their ancestral estates, regardless of whom they love. A domineering woman controls the family’s money and ruins everyone’s lives. A lower-class woman marries the wrong man and is brutalized into committing crimes, or enabling them. Collections of family jewelry are responsible for multiple murders; family heirlooms and even hidden treasure troves are concealed and there is a deadly race to possess them. (And Miss Silver usually mentions the lust for gain in the spirit of Cain.) A foolish middle-aged woman contracts a romantic attachment to the wrong man. And one unusual theme recurs at least twice as the central premise of a book; if Wentworth tells us about a distinctive and striking garment, like the eponymous Chinese Shawl or a coat with a pattern of huge checks, the next person to borrow that garment is found dead after having been mistaken for its owner.

Again, I think this is the same sort of thing as the constant insistence upon the rich peacock blue of Miss Silver’s drawing room curtains. “A domineering woman controls the family’s money” and ruins everyone’s lives is a plot structure that recurs multiple times; partly because Wentworth knew that this plot would be understood and accepted by her audience, but also because it allowed her to ring a set of changes upon the basic structure and give a different answer each time. (Once, in a clever reversal, the domineering woman at the heart of the family is the only good character and trying to do right by her greedy relatives.) Wentworth understands that the very familiarity of the plot structure is one of the things that attracts her readers. A couple of times throughout her oeuvre, she has a character who is a writer of popular fiction, usually female; these characters casually mention the virtues of writing the same thing over and over.

There is a lot in the 32 volumes about the interaction of social classes, especially in the period immediately after World War 2 when such things were in upheaval in Britain. To be honest, that is more analysis than I’ve had opportunity to do, and it’s such a huge and complex topic in Wentworth, I’m not sure it’s worth the trouble since the reader could attain similar insights at less trouble by merely reading 32 novels. It’s clear that Wentworth is writing for a middle class audience, and flattering them by having it an implicit condition that the reader is familiar with the foibles and habits of the upper classes and despairing of the charming shortcomings of the lower classes. The novels document the poisonous interactions of upper-class families who have more airs and graces than capital, to be sure, but they also depict the painful gentility of the lower classes in attempting to get their children usefully married and established in useful and long-term careers like farmer or housemaid. And when the upper and lower classes intersect, it takes the middle-class Miss Silver — we are always reminded that she’s an ex-governess — to penetrate beneath the social conventions of upper and lower classes and find out the truth. Housemaids cannot reveal what they saw in the dead of night because they were canoodling with the butcher’s boy, and mother cannot know. Scallywag low-class men steal the savings of servant women by marrying them and buying a motor garage. And the young daughters of good families occasionally fall in with the wrong man and ruin their chances at marriage, or meddling mothers insist that their daughters marry men for money with whom they’re not in love. There are occasional partnerships between classes; a repeating theme is a middle-aged woman with a personal servant who is slavishly devoted to her needs (and this includes Miss Silver herself, who constantly takes pride in her housekeeper’s scones). But all classes have their good and bad, both characters and relationships.

There’s more analysis here, but there is so much going on that it will take a long time to consider the entire oeuvre and tease out the strongest strands. So when it comes to why is this particular volume worth reading; honestly, I think it is, if you enjoy the traditional gentle English village mystery with a not-especially-troublesome solution. Taken on its own, this is light and pleasant reading. But I cannot recommend this one volume without also strongly urging you to commit to … well, perhaps not all 32, but enough of a representative sample to let you understand exactly what Wentworth’s skills were and where her focus was constantly applied. One book is interesting, but all 32 form an enormous portrait of social change, changing circumstances, wealth and poverty and gentility and criminality. And all focused around an ex-governess of exquisitely rigorous gentility with a mind like a steel trap.

My favour ite edition

ite edition

To the great dismay of some, I seem to have a particular fondness for a peculiar paperback design concept — one with photographic illustrations of the corpse, posed with a model as the deceased would have been found. I can’t explain it; perhaps it’s something to do with my affection for the level of cheesiness in general in paperback design from about 1939 to 1990. I love the lurid, and having a real person painstakingly posed as a corpse — delightful. Coronet has produced one of my favourite editions of this style in a uniform edition of Wentworth from the 1980s, and while some are disappointingly banal, others are quite exciting examples of good design coupled with that enjoyable concept. The cover depicted here, in shades of green with brown and red accents, has a composed rectangularity that is not often found in designs of this period and I think it’s one of the best of the series.

Note: I have been detected in an error by a sharp-eyed lady in my Golden Age Detection Facebook group, Carolyn Bean, and have corrected a description of the relationship between two characters. I can only say it’s the effect of reading great heaps of these novels one after the other; after a while every handsome young man’s relationship with a beautiful young woman kind of blurs together. Thanks, Carolyn, and I appreciate your mentioning it; my apologies to my readers for the slip-up.

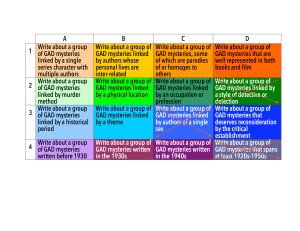

October 8 Challenge

October 8 Challenge

I’ll be claiming this post as an entry in my own October 8 challenge; the lower right-hand corner, a group of novels that spans the 1920s to the 1950s.

Dear Noah. I’ve read many of the Wentworths, and indeed I enjoy them for some of the reasons you mention, especially “the fineness of the writing.” Her writing is smooth, clear, grammatical, and expressive. While it may be quiet and genteel, a Wentworth novel is never dull, thanks to her vivid characters and sense of the dramatic. And yes, there is a “sitting around the campfire” feel of hearing the same Miss Silver facts repeated yet again– clothes and knitting and cough and Tennyson. (Once I did Google image searches for the pictures in Miss Silver’s parlor, what a scream, and how appropriate they looked….) Really, I admire the great professional craftsmanship of Patricia Wentworth, and after slogging through some long padded sloppily written modern “mystery” full of angst and extraneous detail, it is a blessed relief to return to her novels. Yours truly, Tom Sharpley. P.S. I’m a man.

(smiling) I am too, and I like them. We’re just the 10% minority is all. I like your image of “sitting around the campfire” — very apt.

I really enjoyed your analysis of the Silver books Noah – but I have to add, I enjoyed it a hell of a lot more than I did actually sampling one of the books. Everything you say about the Wentworth style, the emphasis on the stifling on social mobility for women and psychological pressure brought to bear on female characters, the quotations, the coughing, structure, the nasty murder victim etc etc were all present and correct in THE IVORY DAGGER, but I found it almost completely confoundingly dull – do you think she meant the revelation of the murderer to be such a thundering awful cliche? Did I pick a duff one from the series? Am I, despite loving Carr and Allingham and greatly enjoying Sayers and Christie, not actually a ‘cozy’ person? Because the last Ngaio Marsh book I read (FALSE SCENT) just was also, in my view, very poor, so I am being unlucky or it’s all a matter of taste …

Well, no, I think False Scent is quite poor, although it has its moments. But ultimately I think it’s a matter of taste, and I can certainly understand readers — especially male readers — finding Miss Silver novels slow and dull.

Thanks for that. So, is IVORY DAGGER representative then?

Hmm. I think they’re ALL representative, although Curtis Evans, I think, is right to suggest that the first three or four in the series are more thrillers than mysteries. I’d have to say that “The Ivory Dagger” is fairly representative and so I doubt you’ll be wanting to plough through the rest; sorry you don’t enjoy them like I do.

That’s really illuminating Noah – I’m particularly interested and impressed by your perception of the small-scale jeopardies of women, I think that’s a most useful idea. If anything could make me read more of her, it’s this blogpost! Thanks.

Thanks, Moira, I appreciate that. I hope you come to like her work as I do.

“Patricia Wentworth is writing for a middle class audience, and flattering them by having it an implicit condition that the reader is familiar with the foibles and habits of the upper classes and despairing of the charming shortcomings of the lower classes.” So much subtler than the usual “They’re all SNOBS!” Also highlights that writers aiming for a middle-class readership must flatter the reader. 😉

Although I’m flattered that you would think I’d isolated a determinative principle, actually I think there are couple of other ways to approach writing for a middle-class readership. One is to write “above” them, which is what I think writers like Iris Murdoch and Patricia Highsmith do — cloak ordinary stories in obfuscatory and opaque language, making everyday events seem somehow more intellectual because of the language. One of my favourite quotes about detective fiction is from Mrs. Q. E. Leavis, who said about the work of Dorothy L. Sayers (I’m not quoting exactly) “that it presents the appearance of intellectual activity to readers who would very much resent such activity if they were actually forced to undergo it.” I think some writers write to demonstrate to their readers that they’re smarter and “here’s something you can learn”. Wentworth at the very least maintains a strong focus on entertaining the reader!

And I’ve got to read them now! Only one I’ve read was set in a superbly drawn artists’ colony with some children in peril and a rather tedious plot strand about a ghostly hand…

[…] Elsewhere I have talked about my fondness for the 32 volumes about the elderly governess/private investigator Miss Maud Silver, written by Patricia Wentworth between 1928 and 1961. I’m very familiar with all those books and have read them numerous times. However, over the years, the 33 volumes by Wentworth that were not mysteries have, by and large, escaped me. Only a handful were ever printed in paperback and, while I was grateful for the chance to appreciate them, I felt that they were really only suitable for Wentworth completists, as it were. (Oh, sorry, I did promise you “no more Mr. Nice Blogger,” didn’t I? The few I read were tedious and melodramatic, a deadly combination.) I had not felt compelled to seek out the expensive and scarce remainder until recently, when a large number of them became available as e-books. My appreciation for Wentworth’s plotting craftsmanship and clear-spoken writing skills has deepened over the years, and I thought I would pick up a couple of these and give them a try, to see if my potential enjoyment had deepened. It had indeed; I loved this book. Here’s why. […]

[…] lady who had a career as a governess before becoming a private investigator. Yes, seriously. Here and more recently here, I have commented upon my admiration for her works. But one thing I […]

I’m a Miss Silver fan from waaay back and came over from the Clothes in Books blog. (BTW Inspector Lamb was Frank Abbott’s superior at Scotland Yard. Randal March was the head of a county police force.) i enjoyed your analysis but wanted to add a thought. I just love the idea of a dowdy older woman running circles around the police force (and of course around the criminals too). A character that a lot of people, especially men, would barely notice–the invisible woman–gets to save the day.

[…] to their children; one is played for laughs and the other is pathological. This hearkens back to something I’ve observed about Wentworth’s work before, in that she knows how to construct “situations that a woman especially would experience as […]

[…] Mystery (1925) (a non-Miss Silver mystery); Poison in the Pen (1954); and a long piece about Miss Silver Comes To Stay (1949) that contains quite a bit of general observation about her entire oeuvre. I’m […]

[…] man and heads to the altar. I’ve written about Miss Silver before, and in quite some detail here in an analysis of Miss Silver Comes To Stay (1949), so if you want my generalized look at all 32 […]